I Would Strike the Critics If They Insulted Me: Contemporary and Modern Criticism for Herman Melville’s Moby Dick

By: Adam Clark Edwards

A popular idiom states that greatness stands the test of time, meaning that great things will be appreciated or revered for generations after it is produced. While this definition of greatness has its merit, it does not necessarily mean that all great things will be appreciated at all times. In fact, many great things were not always appreciated. One example of this is Hall of Fame NBA legend, Scottie Pippen. Pippen won six NBA titles alongside Michael Jordan in his career but his greatness was not always known. Out of high school, Pippen did not receive any scholarship offers and his only option to continue his basketball career was to walk on with a small school in the University of Central Arkansas (Fluck pp. 9-11). Another example is rock band Velvet Underground’s debut album, Velvet Underground & Nico. The album featuring frontman Lou Reed was initially considered a failure both financially and critically. Many stores banned the album because of its controversial subject matter and many radio stations refused to play it because they feared the innovative sound would alienate listeners. However, since that time, the album has been considered a masterpiece. RollingStone Magazine placed it 13th on its list of the 500 greatest albums of all time (RollingStone, pp. 87). There are many other examples of this popular culture.

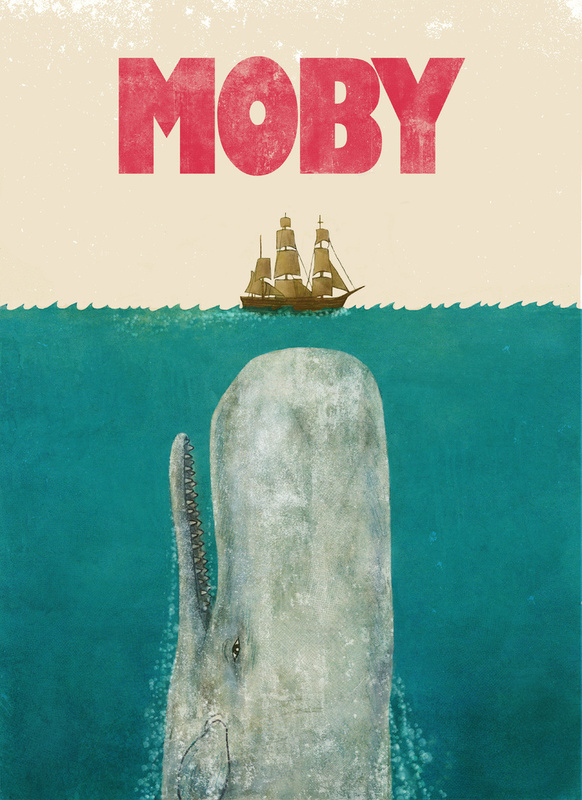

The truth that greatness can be overlooked, though, extends beyond popular culture and into the high arts. A classic example of this is Herman Melville’s novel, Moby Dick. The novel was first published in 1851. By this time, Melville was already an acclaimed writer for his works Typee and Omoo. Melville was looking to further his success as a novelist with Moby Dick but the reception was disappointing. The novel was first published in Britain, printing 500 copies. The first four months sold less than 300 copies. This could partly be due to the scathing review from British literary critic, Henry F. Chorley. Chorley said:

This is an ill-compounded mixture of romance and matter-of-fact. The idea of a connected and collected story has obviously visited and abandoned its writer again and again in the course of composition. The style of his tale is in places disfigured by mad (rather than bad) English; and its catastrophe is hastily, weakly, and obscurely managed... We have little more to say in reprobation or in recommendation of this absurd book... Mr. Melville has to thank himself only if his horrors and his heroics are flung aside by the general reader, as so much trash belonging to the worst school of Bedlam literature—since he seems not so much unable to learn as disdainful of learning the craft of an artist. (Chorley)

One of the problems that faced Moby Dick amongst British readers is that the epilogue was omitted in the British publication. Many thought that the narrator, whom we are told to call “Ishmael,” had died along with the rest of the crew of the Pequod; they wondered how “Ishmael” could transcribe his story to print when he is dead. This is one possible reason why it initially reviewed so poorly.

Chorley’s review was a major blow to not only Melville, but to all of America. In 1820, Scottish critic Sydney Smith published an article in the Edinburgh Review titled, “Who Reads an American Book?” Smith says, “The Americans are a brave, industrious, and acute people; but they have hitherto given no indications of genius, and made no approaches to the heroic, either in their morality or character” (Smith pp. 1). Smith’s review hit a sensitive spot in many Americans’ artistic inferiority complex.

Between Chorley and Smith, it appeared that Moby Dick was going to land into obscurity. It did get filed into the American obscurity folder for rest of Melville’s life; only 3,715 copies were sold at the time of his death in 1891 (Seder pp. 9). After Moby Dick, Melville wrote two more follow up novels in Pierre: or, The Ambiguities and a lost manuscript that was never published. Pierre also received poor reviews, causing Melville to leave writing novels and pursue a steady paycheck from publishing short stories. Between 1853 and 1856, Melville published fourteen short stories in Putnams and Harpers magazines, including Bartleby, the Scrivener. Melville would write and publish one more novel in The Confidence Man but it also received little to no acclaim when first published. Most of Melville's career left him desiring the elusive recognition that he deserved.

Moby Dick did receive some positive reviews, though, when first published. One of these came from fellow writer, Nathaniel Hawthorne. Hawthorne said, “What a book Melville has written! It gives me an idea of much greater power than his preceding ones” (Miller 354). Although one could argue that Hawthorne is expressing his bias in defending his country (Hawthorne was American), his friend (Hawthorne and Melville were neighbors), and himself (Moby Dick was dedicated to Hawthorne; who wants to be associated with a poorly reviewed novel?), perhaps Hawthorne was in the minority that recognized the genius in Moby Dick.

It wasn’t until 1892, a year after Melville’s death, that Moby Dick started to gain notoriety. Moby Dick, along with Typee and Omoo, were reprinted in New York City. It became very popular in New York’s literary community that kept it in circulation long enough for both World Wars to come around. Each war saw a new appreciation for Moby Dick as it dealt with philosophical and moral themes associated with the wars. In his 1941 book, American Renaissance; Art and Expression in the Age of Emerson and Whitman, F. O. Matthiessen observes, “Moby-Dick was now read as a text that reflected the power struggles of a world concerned to uphold democracy, and of a country seeking an identity for itself within that world” (Matthiessen). In a time where people saw morals succumb to evil, it was easy for them to identify with “Ishmael” trapped in an environment with Captain Ahab commanding the microcosm of the world, The Pequod.

Moby Dick is now considered one of, if not the best, American novels. The opening line, “Call me Ishmael,” is one of the most famous opening lines in all of literature. The fame of Moby Dick has found its way into popular culture in many places including the 1956 film with the same name, starring Gregory Peck. References to novel have also been found in art, film and television shows including The Simpsons, Futurama, Family Guy, and Star Trek. The novel will continue to a dominating presence in academics and popular culture. It is funny to think that one of the greatest novels of all time was once considered a shipwreck.

Bonus: A brilliant analysis of Moby Dick by Sparky Sweets, PhD.

Sources

“500 Greatest Albums of All Time.” Rollingstone.com. RollingStone, Nov. 2003. Web. 20 Oct. 2014.

Chorley, Henry F. London Athenaeum, October 25, 1851. Web. 20 Oct. 2014.

Fluck, Adam. “Donald Wayne: Scottie Pippen Is Making Hamburg Proud.” nba.com. NBA, 10 Aug. 2010. Web. 20 Oct. 2014.

Matthiessen, F. O. American Renaissance; Art and Expression in the Age of Emerson and Whitman. London: Oxford University Press, 1941. Print.

Miller, Edwin Haviland. Salem Is My Dwelling Place: A Life of Nathaniel Hawthorne. Iowa City: University of Iowa Press, 1991. Print.

Seder, John. “11 Early Scathing Reviews of Works Now Considered Masterpieces.” mentalfloss.com. Mental Floss, 20 April 2012. Web. 20 Oct. 2014.

Smith, Sydney. “Who Reads an American Book?” The Edinburgh Review 33 (1820): 69-80.